Design for Transformation

Cultivating enduring wellness behaviors in young adults

Abstract

The wellness industry in the United States sits at an estimated 1.8 trillion dollars in value as of 2024, with wellness spending showing significant gains among Gen Z and Millennial consumers. Despite its widespread commodification in contemporary consumer society, wellness as a pursuit of growing significance presents an opportunity for novel and creative approaches to improving overall health and wellbeing. This research seeks to identify key processes that foster sustained wellness habits in young adults, with consideration paid to the role of technology in promoting or obstructing wellness goals. This survey and interview-based study makes use of participant insights to map out the relative influence of material, social, and digital factors in the transformation of mindsets, habits, and states of being towards improved overall wellness. Furthermore, this work aims to inform a design framework towards creative strategies that cultivate physical, mental, and social wellbeing while considering the pressures presented by a consumption-based wellness culture and a life increasingly online.

Introduction

From the taglines of alternative health products and mantras of online microcelebrities, to the lingo of the corporate workplace, the concept of “wellness” has penetrated numerous facets of contemporary life. Despite drawing inspiration from time-honored traditional health practices and 20th century activist and counter-cultural philosophies, modern wellness culture has found itself squarely the domain of mass consumption (Baker, 2022b). This is reflected in the market, with the US wellness industry sitting at an estimated 1.8 trillion dollars as of 2024 (Global Wellness Institute, 2024). While the wellness industry thrives, modern consumers face a matrix of physical, social, and emotional ailments for which they are marketed a dizzying array of consumable remedies. Interest in this sector is growing across younger generations, with the promise of improved wellbeing through mass marketed products, services and experiences having captured the imagination and dollars of Millennial and Gen Z consumers, who outspend older generations on wellness-related purchases (Segel & Hatami, 2024).

As a result of the capitalist takeover of wellness, the pursuit of holistic health and wellbeing has become a matter of lifestyle and individual consumer choice, manifesting as an endless carousel of new and exciting wellness products to be tried, tested, duped and discarded. The growth of the wellness industry hinges on the emergence of new problems and new solutions in perpetuity, complicating the goal of existing holistic health interventions to produce sustained positive change in people’s lives. Such a commodified wellness landscape might place limitations on the capacity for truly transformative and sustainable holistic health innovations, particularly in an era where the downtime necessary for such pursuits is diminished by the omnipresence of digital media and technology. Yet, despite these barriers, the promise of self-improvement and personal enrichment through self-care has proven itself a motivating force.

The possibility for profound personal transformation presented by the wellness industry has captured the attention of young adults, a demographic that has demonstrated increased interest in this trillion-dollar industry through their wellness spending. Young adults face a distinctive set of wellness concerns, including increased rates of mental health issues and deeper entrenchment in the “attention economy” produced by the ubiquity of digital media in their lives (Liang, 2024). The role of mobile technology and social media in contemporary wellness culture cannot be overlooked, as it often serves as the engine for the industry and its trend cycles. When imagining novel approaches to wellness that foster long-term improvements to overall wellbeing and healthy habit formation, it is important to consider the way technology influences health and the opportunities presented by its ubiquity and convenience. Addressing the limitations presented by both commodification of wellness, and reliance on technology that characterize the wellness space for young adults, might involve replacing trend-based patterns of overconsumption with creative or socially engaging alternatives.

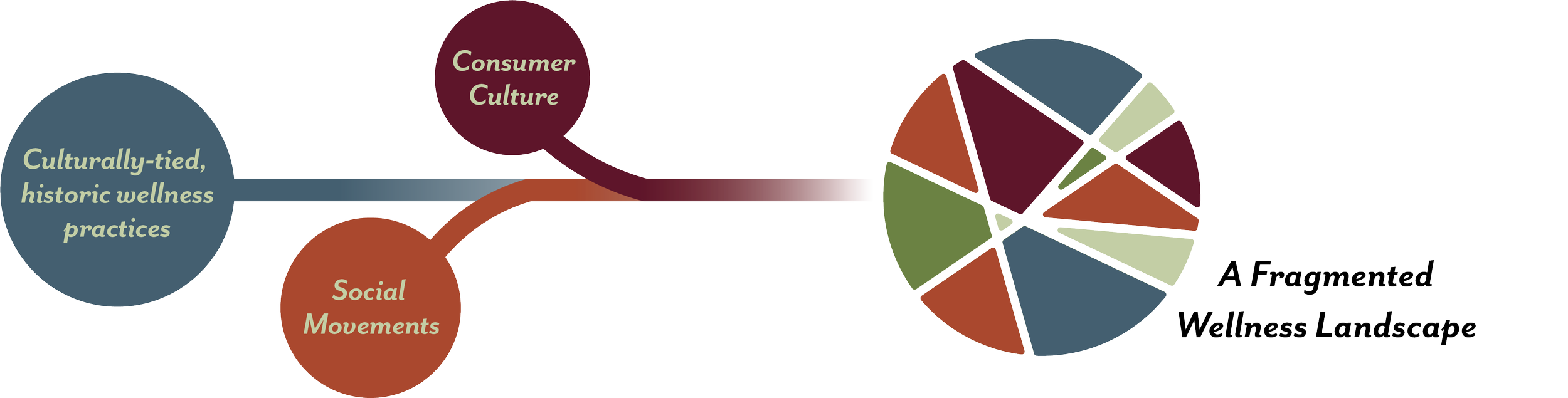

The conflation of the “wellness-industrial-complex” with holistic health practices more broadly is a modern phenomenon, the result of the commodification of those practices and the stripping away of their original cultural context. This process has led to the fragmentation of the wellness landscape, where opportunities are presented independently of their history, purpose, and relationship with one another, leaving consumers at times aimless and susceptible to marketing schemes, pseudoscience, and overconsumption (Baker, 2022b).

From this premise the following question emerges: when entering traditional wellness communities is impractical or inappropriate, what opportunities might those seeking improved overall wellbeing have to take on and sustain new routines without falling into patterns of overconsumption? One possible approach to answering this question is to identify what key factors and processes make it possible for individuals to successfully implement wellness routines into their lives despite the limitations brought forth by commodification and the growing influence of technological distractions. Understanding what makes for a successful personal transformation can help to inform a framework that designers can use to get at the heart of user concerns rather than bandwagon off the latest consumer trends (Coffey, 2024) The purpose of this thesis is to develop this framework of self-discovery based on data from a multi-modal qualitative research study. This work will center around the unique experiences and perspectives of individuals aged 18 to 34 years old, taking note of this demographic’s growing interest in the wellness industry and relationship with technology. Centering on younger adults also supposes the relative prominence of preventive health and wellness concerns over curative healthcare that may be more pertinent to older individuals.

In a two-part research protocol, including a survey and semi-structured interviews, my methodology includes developing a baseline understanding of the perceptions and role of wellness in the lives of young adult participants aged 18-34. With a smaller subset of survey participants, I will then conduct interviews to further define the key needs, actions and considerations under which new wellness routines are adopted and solidified into an individual’s overall lifestyle. Qualitative data from each phase of the protocol will be analyzed, with a specific focus on the limitations and opportunities posed by both the commodification of wellness culture and the role of technology in aiding or restricting personal transformation. Through this analysis I will address the following hypothesis:

Solutions that transform and personalize wellness products and services through creative practices and social engagement offer more effective and sustained healthy habits.

The framework developed by the summation of the qualitative data from this study will then be used in conjunction with design thinking strategies to prototype novel methodologies for introducing and sustaining healthy habits in young adults that prioritize impact over profit

Research Questions

The foundational research question for this project can be summarized as follows:

What are the most effective mechanisms for incorporating sustained wellness habits into the lifestyles of young adults?

Additional sub-research questions to be considered in this work include those aimed at understanding the cultural context around wellness and its role in the lives of young people and the landscape of contemporary consumer society. For instance, through a combination of primary and secondary research, I also seek to address the following within the context of my topic:

How do these young adults define wellness and make a place for wellness products, services and practices in their lives?

How does the use of social media and mobile technology impact the maintenance of wellness habits and routines?

How do some young adults view their efficacy in managing their own health and wellness? What attitudes do they espouse that support or limit them in setting and achieving goals in this area?

How does the commodification of wellness in contemporary consumer society influence the attitudes and behaviors of this group of young adults?

Literature Review

What is Wellness?

The term “wellness,” while ubiquitous and evocative, is relatively vague. In one of the earliest uses of the term, Halbert Dunn conceptualizes wellness as “an integrated method of function which is oriented toward maximizing the potential of which the individual is capable, within the environment where he is functioning” (1959, p.447). Dunn emphasizes not only the “freedom from illness” which constitutes wellness, but the “condition of change in which the individual moves forward, climbing toward a higher potential of functioning” (1959, p.447). An action-oriented and totalizing understanding of wellness remains pertinent, yet our concept of wellness is complicated by its dynamic associations with both modern and traditional health practices, ever emerging lifestyle philosophies and complex measures of holistic wellbeing, all existing today within a broader consumer culture. Thus, the definition of wellness I will use to ground this work includes the growing role of the wellness industry in shaping individual and collective journeys towards greater overall wellbeing. This approach considers how wellness cultures in the United States are filtered through the apparatus of consumerism, even when drawing inspiration from sources ranging from ancient tradition to revolutionary conceptions of self-care (Baker, 2022b). With this in mind, I have adapted a definition of wellness articulated by Grénman et al. (2019) in their investigation of wellness consumption as a means of self-branding. In this thesis, wellness is understood as a holistic approach to optimizing health and well-being through transformative consumption. Highlighting the transformative dimension of wellness is crucial for the work that follows, where design opportunities harness the enduring potential for revolutionized physical, mental, and spiritual wellbeing despite the capitalist capture of wellness.

In the popular imagination, wellness encompasses the broad category of holistic health, sometimes paired with a focus on natural health alternatives or preventive health, and is understood as distinct from medicine (Baker, 2022b). While this project investigates what wellness means in the lives of young people today, the historical manifestations of “wellness culture” can serve to illuminate the origins of the way we think about good health and the strategies by which we achieve it. Wellness tends to imply a sense of internal balance, a notion that calls back to the medical approaches of the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates whose treatment approach involved not only the famous mantra “do no harm” but sought wellness through the balancing of the body’s four humors (Baker, 2022b). Other traditions that mirror this approach include Ayurveda, an ancient Indian healing tradition, and Traditional Chinese Medicine, both of which are practiced to this day and are enduring methodologies for achieving spiritual and bodily harmony through the balancing of internal forces (Baker, 2022b).

While these ancient examples highlight some of the underlying principles we continue to associate with wellness culture today, the trajectory of wellness in the United States can be further understood through reflection on a series of relevant social and cultural movements over the last several centuries. For instance, nineteenth century America saw the rise of “alternative medicine,” where novel and often dangerous therapies emerged, in part, from a rejection of the mainstream medical system, coinciding with the rise of new spiritual movements (Baker, 2022b). In the 20th century, the philosophy of “self-care” (Baker, 2022b, p.22) would further penetrate alternative health circles, taking a form that may be familiar to a contemporary wellness enthusiast. The Civil Rights Movement saw an emphasis on accessible, community-based care and the reclamation of the body for those marginalized by poverty, racism, and misogyny (Baker, 2022b). The notion of self-care, which still carries with it the memory of its feminist origins in contemporary holistic health circles, has persisted as a relevant term in wellness culture and has been adopted into the language of the wellness industry (Badr, 2022). Despite having origins in the civil rights and counter-cultural landscape of the mid-20th century, wellness culture today has made a decisive turn towards mainstream capitalist capture. This multi-trillion-dollar global industry largely generally concerns itself with individualistic rather than collective wellness goals, despite drawing heavily from the methods and products of traditional cultures and social movements (Badr, 2022; Baker 2022b).

Navigating a Fragmented Wellness Landscape

With this brief history of wellness culture in mind, we can begin to solidify a theory of the role of wellness in contemporary consumer society. Wellness as an interconnected, holistic perspective on health involving piecemeal approaches to achieving healthy outcomes can be theorized within a wider postmodern tendency towards fragmentation and decentralization (Thompson & Troester, 2002). Instead of coalescing around a singular, historically grounded health practice or system of practices, contemporary wellness culture is highly adaptable, self-reflexive, and market-driven (Thompson & Troester, 2002; Badr, 2022). In addition to providing a highly customizable, individualistic approach to self-improvement and self-care, wellness consumption and practice is integrated into contemporary culture through its relationship to work and a moral imperative directed towards increased productivity and personal optimization (Smith et al., 2024).

Figure 1. The fragmentation of wellness in contemporary consumer culture

This phenomenon can be readily observed in the wellness incentives programs taken up by corporate employers as a way of investing in employee productivity (Smith et al., 2024). The corporatization of wellness culture pushes against the goal of improved holistic wellbeing and the virtues of feeling good within oneself and replaces it with the goal of achieving a more perfected and optimized self that can be captured in numerical terms.

Just as standard medical care has become increasingly entwined with neoliberal market-based mechanisms, so has the practice of self-care through the forces of both commodification and medicalization (Cavusoglu & Demirbag-Kaplan, 2017). In their analysis of wellness micro-cultures through the examination of social media posting on wellness, Cavusoglu and Demirbag-Kaplan (2017) identified two key axes upon which representations of wellness consumption online could be mapped, namely, a spiritual wellbeing to bodily wellbeing axis and a “communification” to commodification axis. Communification and commodification both describe meaning-making processes taken on by consumers, who can use the apparatus of social media to invent themselves as responsible and health-conscious consumers through engagement with wellness communities and commodities (Cavusoglu & Demirbag-Kaplan, 2017).

While community health had, at one point, anchored wellness discourses, the centering of the individual characterizes much of the wellness landscape today. This inward focus, which stresses self-optimization, manifests in several ways. This manifestation includes the transformation and idealization of the physical body to the creation of a personal brand. Sociologist Mike Featherstone asserts that consumer culture emphasizes a “self-preservationist conception of the body” (1982, p.18) which privileges strategies for combating deterioration and decay. Those strategies or routines not only allow for the body to project youth, beauty, and health, but enhance the expressive capacity of the body (Featherstone, 1982). Sociologist Roberta Sassatelli reflects further on the role of “active leisure” in molding the body into something culturally appropriate through commercialized leisure, manifesting as habit-tracking applications, personal trainers, and gym memberships (2016). The treatment of the body in this way can prove to be oppressive in its rigidity and can provide ammunition for advertisers looking to exploit consumer insecurities. Social appropriateness is similarly relevant in the relationship between wellness and pleasure, where feeling good has found itself to be a socially insufficient motivator for wellness practices (Smith et al., 2024). Under the regime of discipline and self-responsibility, we experience a “domestication of pleasure” (Smith et al., 2024, p.104) in which there exists a narrow scope of acceptability between unpleasantness and hedonism in contemporary wellness culture

While the fractured and individualistic nature of contemporary wellness culture produces certain boundaries and limitations around genuine engagement with transformative and fulfilling practices, the current paradigm also supports an expressive and creative dimension of the performance of self through self-improvement and self-optimization. This is explored by Grénman et al. (2019) in their study on wellness as a means of self-branding. In taking this perspective on wellness, the integration of a set of practices that promote balance, fitness, mindfulness, and self-improvement feed into the cultivation of an idealized goal of the “optimal, balanced self” (Grénman et al 2019, p. 472). Though the challenges presented by the commodification of wellness place serious limitations on this utopian point of view, the relationship between healthy goal setting and the imaginative performance of self provides uniquely creative opportunities to promote personal transformation.

As touched upon earlier, the role of digital media and technology, and especially social media, in creating the fragmented wellness landscape cannot be overstated. One mechanism by which it profoundly influences sociocultural perceptions of the body is through the proliferation of images. Though predating the advent of the modern internet, this passage from Featherstone (1982) distills the immense impact of these images:

…with regard to the proliferation of images which daily assault the individual within consumer culture, it should be emphasized again that these images do not merely serve to stimulate the false needs fostered onto the individual. Part of the strength of consumer culture comes from its ability to harness and channel genuine bodily needs and desires, albeit for health, longevity, sexual fulfillment, youth and beauty represent a reified entrapment of transhistorical human longings within distorted forms (p. 30)

In this dynamic, image-centered and consumption-fueled world, influencers and microcelebrities not only sell their highly aestheticized, idealized lifestyles but a piece of themselves through the uniquely intimate relationship they cultivate with their audiences (Baker, 2022b; Spulveda et al., 2025).

These examples of fragmentation and the co-option of the wellness demonstrate how contemporary wellness culture is rife with contradiction. Social scientists have sought to better understand how individuals navigate these contradictions when approaching their own holistic health and strategies towards improved wellbeing. In a qualitative interview-based study conducted by communications researcher Colleen Derkatch, the concept of wellness is revealed to be self-contradictory, rendering it a moving target for definition and as a foundation for theory (2018). Derkatch suggests that the way wellness and wellness-oriented habits of consumption are conceptualized and discussed sets up two opposing logics, one of restoration and one of enhancement. In her view, this opposition perpetuates the cycles of consumption that prop up the wellness industry (Derkatch, 2018). Opposition does so by promising both a restoration of basic markers of health and enhancement above and beyond the standards and frameworks of mainstream medicine. Navigating these opposing logics might serve as a foundation for the goal setting strategies of those seeking improved wellbeing as they shape the expression of wellness advice online.

Critical Concerns Among Young Adults

Young adults are in a unique position as wellness consumers, in part due to their exposure en masse to the broader wellness industry, amplified by content sharing on social media platforms (Segel & Hatami, 2024). This is where information on physical and mental optimization proliferates, condensed into digestible pieces of “content”. The consumption of short-form content at a dizzying pace leaves young adults confronting the influence of the digital world and its consequences more than other age groups. This condition shapes the wellness concerns of young people, particularly around social media use and access to information.

For the vast majority of young adults, social media is a fixture of everyday life. In a survey of 14 to 22-year-olds conducted in 2018, more than 9 out of 10 respondents reported using social media, including 17% who say they use it “almost constantly” and 54% who log onto social media platforms multiple times a day (Rideout & Fox, 2018). The monumental role of the digital sphere in the everyday lives of young people is a double-edged sword, contributing both uniquely modern problems and technologically enabled solutions in the realm of health and wellness.

The proliferation of wellness advice, recommendations and trends through the internet and social media is indicative of this ambivalence. The internet is a virtually endless resource for the exploration of wellness advice and information. According to a nationwide survey of teens and young adults, 87% say they have gone online for health information (Rideout & Fox, 2018). A large proportion of those searches are in the realm of physical health, namely fitness (63%) and nutrition (52%), while many young adults also reported using the internet to access content related to mental wellbeing (59%) (Rideout & Fox, 2018). The endless availability of wellness resources online comes with considerable risk, as there is often no guarantee of accuracy and misinformation is proliferated with ease (Lee & Worthy, 2021). These networks of information can grow insidious, as exemplified by the weaponization of alternative health discourses towards the conspiratorial thinking and far-right extremism that emerged prominently during the COVID-19 pandemic (Baker, 2022a).

The demonstrable harm caused by wellness culture through misinformation campaigns like those orchestrated by alternative health influencers in the COVID-19 era should be cause for skepticism when approaching health and wellness information and communities online. However, the weaponization of wellness discourse that tempts consumers with an illusion of agency and the very real possibility for personal transformation through improved self-efficacy should not be falsely equated. After all, wellness practices have existed for millennia, and while many have since been decoupled from their original context, for better or worse, the internet has provided democratized access to those practices in a way that cannot be ignored. Of course, the values and lifestyle philosophies that consumers pair with their increased access to information is significant. In a qualitative study of young adult’s perceptions of a good life conducted by Grenman et al. (2022), these values are shown to be quite encouraging, with young adults expressing a desire for a “eudaimonic-oriented life” (Grenman et al., 2022, p.1) where moderation, self-discovery and concern for sustainability in consumption practices are paramount. Strategies for maintaining a strong commitment to wellness might take into consideration these value systems by prioritizing self-reflection over runaway consumption

Transformation of Wellness Commodities: A Design Opportunity

Beyond the merits and challenges of the online wellness landscape, consumers that engage with the products, practices and philosophies of contemporary wellness culture are faced with additional tensions and contradictions surrounding consumption. Among young adults, that tension may come in the form of concerns around sustainability and environmental collapse coming in conflict with the very modern desire to distinguish oneself through lifestyle choices and self-expression (Grénman et al, 2022; Grénman et al 2019). However bleak the decoupling of wellness culture from the endless cycle of consumption may seem, there are creative avenues through which designers and consumers alike can rethink engagement with preventative and holistic health, focusing in and facilitating practices that enhance wellbeing through creative and social processes.

Despite the broad commodification and fragmentation of wellness products and services in contemporary society, potential exists for consumers to engage in decommoditization, a process described by sociologist Roberta Sassatelli in which commodities take on new meaning by way of ritual, social and creative reimagining (2007).

Decommoditizing mechanisms might be harnessed by designers to generate effective, affordable, and sustainable wellness interventions that break the cycle of endless consumption - prioritizing the holistic health and wellbeing of consumers by allowing them to adopt wellness rituals and routines into their lives on their own terms.

The “serial intimacy” (p.196)brought about through the process of collecting, sacralization through engagement in ritual, the affirmation of social bonds through gift-giving, and creative personalization of commodities are all examples of decommoditization (Sassatelli, 2007). Considering these mechanisms and their potential within the wellness space, we can consider new possibilities for addressing the barriers to achieving wellness goals in young adults, including cost, mindset, and the endless distractions of the attention economy.

The imaginative reframing of wellness through the lens of personalized transformation calls back to the original conceptualization of wellness by Halbert Dunn. His seminal article highlights the importance of both self-efficacy and imagination in wellness problem-solving, where the wellness journey, a “condition of change” (p.447) is made possible by self-discovery, self-assurance, and a willingness to explore the possibilities when it comes to meeting individual and collective needs (Dunn, 1959). A consumption framework that dictates those needs and provides solutions without the imaginative or creative input of those hoping to improve their overall wellbeing is destined to fall short.

Figure 2. Adding layers of meaning through “decommoditization” processes. Adapted from Sassatelli (2007).

Pilot Study

Purpose

A survey-based pilot study was conducted in December of 2024 to investigate the role of wellness lifestyle and consumption choices in the cultivation of self-identity. This brief exploration of the relationship between consumer culture, identity, and wellness habits served to evaluate and reveal effective strategies for probing consumer experiences with wellness. Data and conclusions drawn from this pilot study would provide background for the development of meaningful research questions, hypotheses, and would serve to highlight central themes that would prove valuable in future, IRB-approved research. Considering a diverse body of theoretical works, my hypothesis was as follows:

Consumer engagement with wellness products, services, and experiences provides an opportunity for cultivation of self-identity through the balance of moral and hedonistic considerations.

Methods

An anonymous survey was distributed over three days via private Instagram story to my extended social circle. A total of thirteen (n=13) surveys were completed. The survey was thematically organized to allow respondents to answer survey questions in a systematic way, building upon previous responses to allow narrative self-explorations to evaluate the central hypothesis. Participants were asked to provide basic demographic information followed by seven open-ended questions. These questions covered key themes including participant definitions of wellness, living well and lifestyle, the role of media in wellness culture, and a concluding question on barriers to achieving wellness goals. Participant answers to definitional questions were coded based on pre-selected themes drawn from a review of the literature and prior theoretical investigations in a direct content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Survey questions prompting further elaboration were textually analyzed to provide context and reveal participant perspectives and thought processes (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005).

Conclusion

Analysis of survey responses revealed the way participants understood the concept of wellness. This foundational inquiry serves to inform key thematic considerations for use in future qualitative research. This pilot study also revealed that invoking the role and influence of the wellness industry directly could potentially stir distrust in participants, discouraging the expression of individualized wellness routines and personal philosophies of wellbeing. Survey and interview design in a formal study should permit natural associations from the personal experiences of participants rather than projections from the theoretical interests of the researcher. The types of questions that generate the most reflective and honest answers from participants should be privileged in later iterations of this study, so that the richest qualitative data representing the lived experience of participants might be collected and analyzed.

Methodology

Worldview and Approach

This study employs a pragmatic worldview, with particular emphasis on problem definition informed by the literature and the use of qualitative data and design thinking to drive solutions (Creswell, 2018). While pragmatism is the guiding philosophy for the IRB-approved, multi-methods qualitative study portion of this research, theoretical perspectives on wellness and its role in consumer culture inform both the hypotheses and guiding research questions as outlined in the introduction.

The goal of the multi-methods research study outlined in this section is to map the key processes that contribute to the adoption of wellness-oriented attitudes and behaviors in young adults, with particular interest in creative, sustainable, and even transformative responses to the commodification of wellness culture and the implications of increased digital technology usage. The mechanisms that bolster the successful integration of wellness routines and behaviors into daily life will be explored through a survey and interview-based protocol. The data derived by these methods is analyzed to reveal the key processes that drive healthy habit formation and intentionality around the maintenance of holistic wellbeing.

Methods

The first part of this study consists of an IRB-approved exempt digital survey designed to identify and collect participant definitions of wellness, reflections on the factors that support the adoption and maintenance of wellness routines as well as insights into successful goal-setting behaviors. In addition to several open-ended response question, the survey includes Likert matrix tables to collect quantitative data about participant experiences with wellness, including the importance of wellness in their lives, the key lifestyle areas wherein they seek improvement to their overall wellbeing as well as the degree to which certain barriers hinder their ability to achieve those desired health and wellness outcomes (To see the complete list of survey questions, please see Appendix A).

The survey was distributed via email and through message chains as part of a snowball sampling with the goal of expanding outward from the academic environment into a variety of contexts. I distributed the survey link and description to professional contacts at Drexel University and the University of Pennsylvania, as well as within the Movement Callowhill gym community. Survey information, disclosures and consent were all included on the digital survey interface and participants were screened for age. In this study, participants were required to be between 18 and 34 years of age to fit the target demographic of “young adult”.

Quantitative data from Likert matrix tables and multiple-choice questions were analyzed via built-in Qualtrics data analysis tools, providing a summary of participant attitudes. In-depth qualitative data was collected from text-response questions, where participant answers were organized, coded, and affinity-mapped to identify recurring themes and patterns of participant experiences with wellness. Further analysis was conducted through an iterative mind mapping process, and participant responses to questions about the adoption and maintenance of wellness habits were organized in a journey map to guide the development of process-based frameworks.

Survey participants were permitted to share their name and email if they were interested in participating in a semi-structured interview after the completion of the survey. Identifying data was stored separately as analysis was conducted. The purpose of the interview was to allow for a richer discussion of participant experiences with wellness, with a particular emphasis on factors that contribute to the initiation, adoption, maintenance, and sharing of wellness habits. Participants were also encouraged to consider their wellness goal setting habits and the potential barriers to achieving those goals. Interviews were conducted remotely on Zoom and were recorded. Transcripts were collected automatically via built-in software while hand written notes were taken to organize key ideas and themes. Qualitative data from interview transcripts were coded, thematized and organized into personas based on distinctive motivating aspects of participant experiences with wellness.

Insights from each phase of the study were then combined to produce process-based frameworks. These frameworks were then used to propose potential habit tracking and journaling protocols that harmonize with distinctive user personas and approaches to wellness goal setting.

Results

Survey

A total of thirty-three (n=33) survey responses were collected via Qualtrics. No demographic information was captured beyond participant age, which was self-reported. 17 (57%) of respondents were 18-24 years old, 10 (30%) of respondents were 25 – 29 old, and 6 (18%) of respondents were 29 – 34 years old.

Defining Wellness

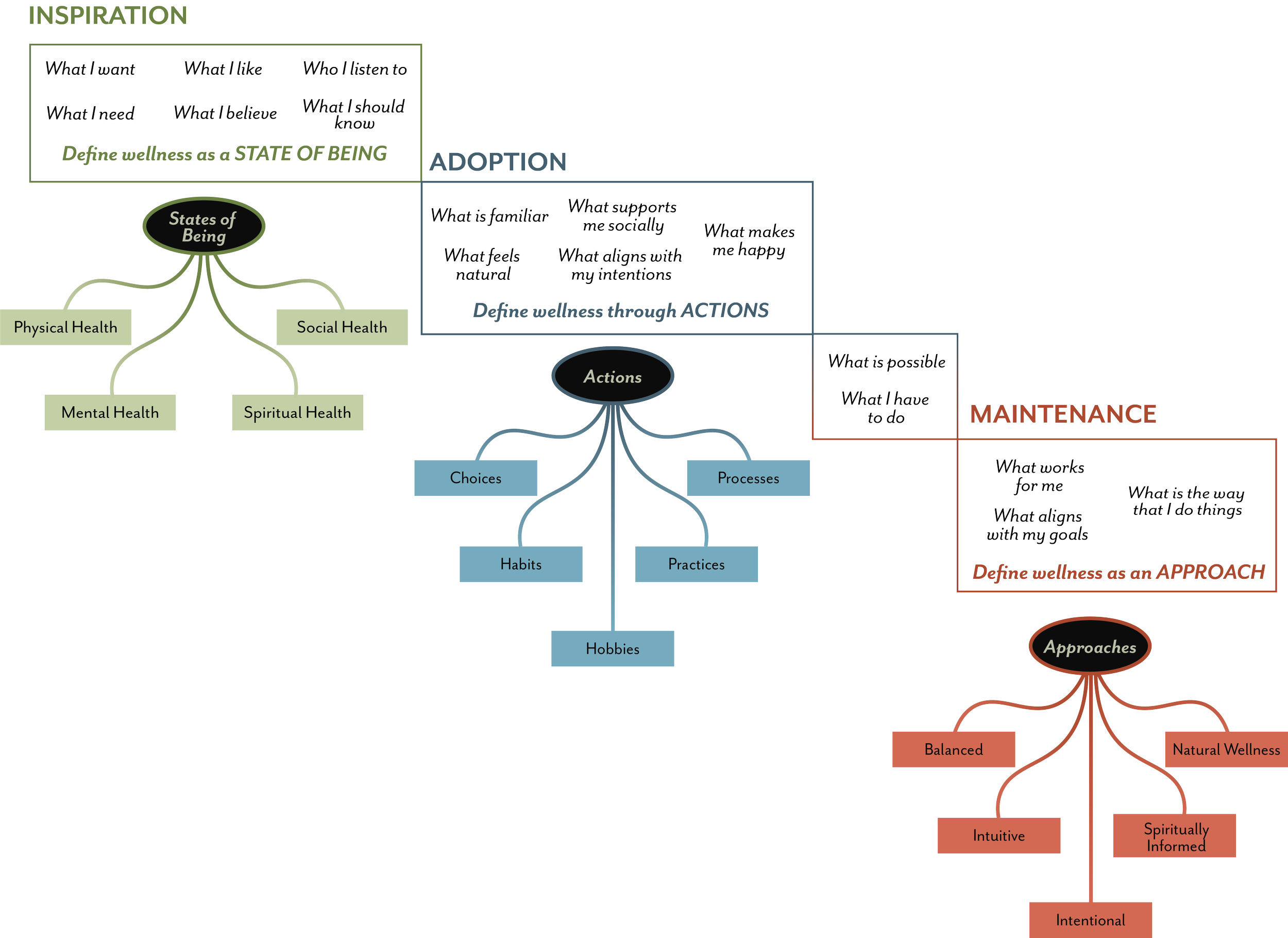

Participants were asked to define wellness in their own words. Responses were coded based on three overarching categories identified in a pilot study: Wellness Actions, Wellness Approaches, and Wellness States of Being.

Wellness Actions

Wellness actions include the choices, habits, hobbies, practices, and processes that individuals engage in as part of an effort to explore, adopt, maintain, and share aspects of a healthy lifestyle. Themes within the category of wellness actions include actions oriented towards maintaining wellbeing, such as “keeping a clear head” or taking “an action that allows one to be ‘healthy’.” Participants also defined wellness in terms of actions that invoke personal responsibility, such as “taking one’s body seriously and making intentional, disciplined, and informed decisions every day about one’s health” and “taking intentional care of my mental, physical, and emotional wellbeing.” Finally, wellness actions could also be defined in terms of sustained habits that contribute to states of wellbeing, for instance, “habits and practices that contribute to [a state of optimal functioning of the mind and body]” or the process of taking steps to secure [the health and wellbeing of the mind].” Ultimately, the articulation of wellness as a set of actions points towards intentionality, will, and a holistic, integrated lifestyle that feeds into both wellness approaches and wellness states of being.

Wellness Approaches

Participants were less likely to define wellness in terms of an approach than they were to define it as a set of actions or a state of being. These definitions took into consideration approaches that prioritize balance, intention, intuition, spirituality, as well as natural wellness. Underlying these categories were participants unique and personalized philosophies of wellness, for instance, one participant indicated that being well meant “using and being able to use your mind and body as nature intended, free of harmful man-made patterns and habits.” Another participant articulated this lifestyle-minded perspective more broadly, stating that wellness is “the position one comes from to then interact with the world around them.” The theme of balance was also a big part of the definition of wellness as an approach, with participants highlighting the importance of “having a good work/life balance” and “having a balanced approach to food, exercise, and mental state that prioritizes wellbeing.” Participants who defined wellness in this manner tended to reflect on their personal lifestyle approaches and the perspectives that guide their actions and contribute to their overall state of health and wellbeing.

Wellness States of Being

Overall, participants were most likely to define wellness as a state of being. Straightforward and often measurable, this understanding of wellness can serve as a foundation for goal setting and provide meaningful benchmarks towards improving overall health. These states of being include physical, mental, spiritual and social health as well as variations and combinations of these categories. Participant responses were organized into themes such as optimal function, as summarized by one participant’s definition of wellness as “a condition of proper function of the body, mind etc, pursuant to longevity, comfort, and lack of illness.” Others highlighted the primacy of mental health specifically, identifying that “someone with good mental wellness is not just happy every day but able to positively cope and navigate through potential stressors.”

Stability and fulfillment were commonly cited as central to wellness, as exemplified by one participant’s consideration of the “ability to feel stable, healthily meet biological needs, and [have] a positive self-disposition.” Some participants ventured more broadly into the lifestyle implications of wellness as a state of being, indicating the importance of “feeling my body active, rested, energetic, combined with maintaining a mental state of peace, curiosity, with the capacity of having a stress tolerance and relief, knowing that every sphere in life must be taken care of to ensure wellbeing.” Finally, the most common way of defining wellness as a state of being was through the lens of holistic health. Many respondents considered how physical, mental, spiritual and social health interact in their conceptions of individual and collective wellbeing.

While participants generally conceptualize wellness as either a set of actions, an approach, or a state of being, these understandings tend to feed into one another and can serve varied functions depending on where in the process of implementing a lifestyle change an individual might be. Wellness as defined in terms of holistic health is comprehensive, involving several key branches that balance to fulfill the health needs and aspirations of an individual; however, these definitions are relatively vague and difficult to translate into meaningful goals and practices. Definitions of wellness that venture deeper into themes such as intentionality, responsibility, fulfillment, and enrichment might better serve long-term commitments to health and support reflection on what it means to be well in young adults, as exemplified by the responses collected in this study.

The role of wellness in the lives of young adults

While the definitions articulated by survey respondents reflect idealized conceptions of wellness, a deeper understanding of the lived experience of wellness of young adults as it pertains to their wellbeing can serve to illuminate processes that support the realization of those ideals, particularly when detached from the narratives of wellness consumption and the holistic health industry.

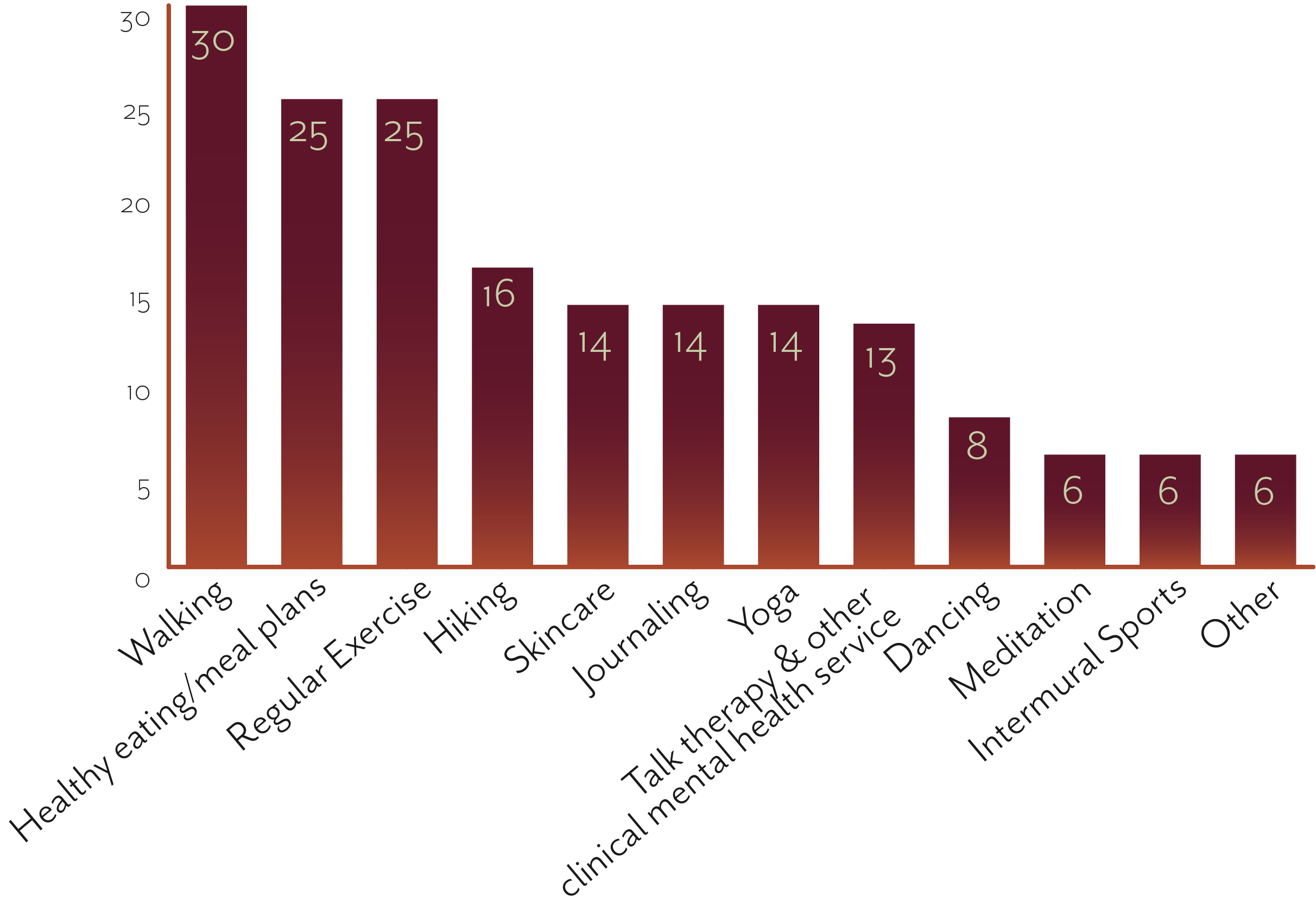

To begin this line of inquiry, participants were asked to identify which wellness activities they actively engage in, with the most common activities including walking (91%), healthy eating/meal plans (76%), and regular exercise (76%).

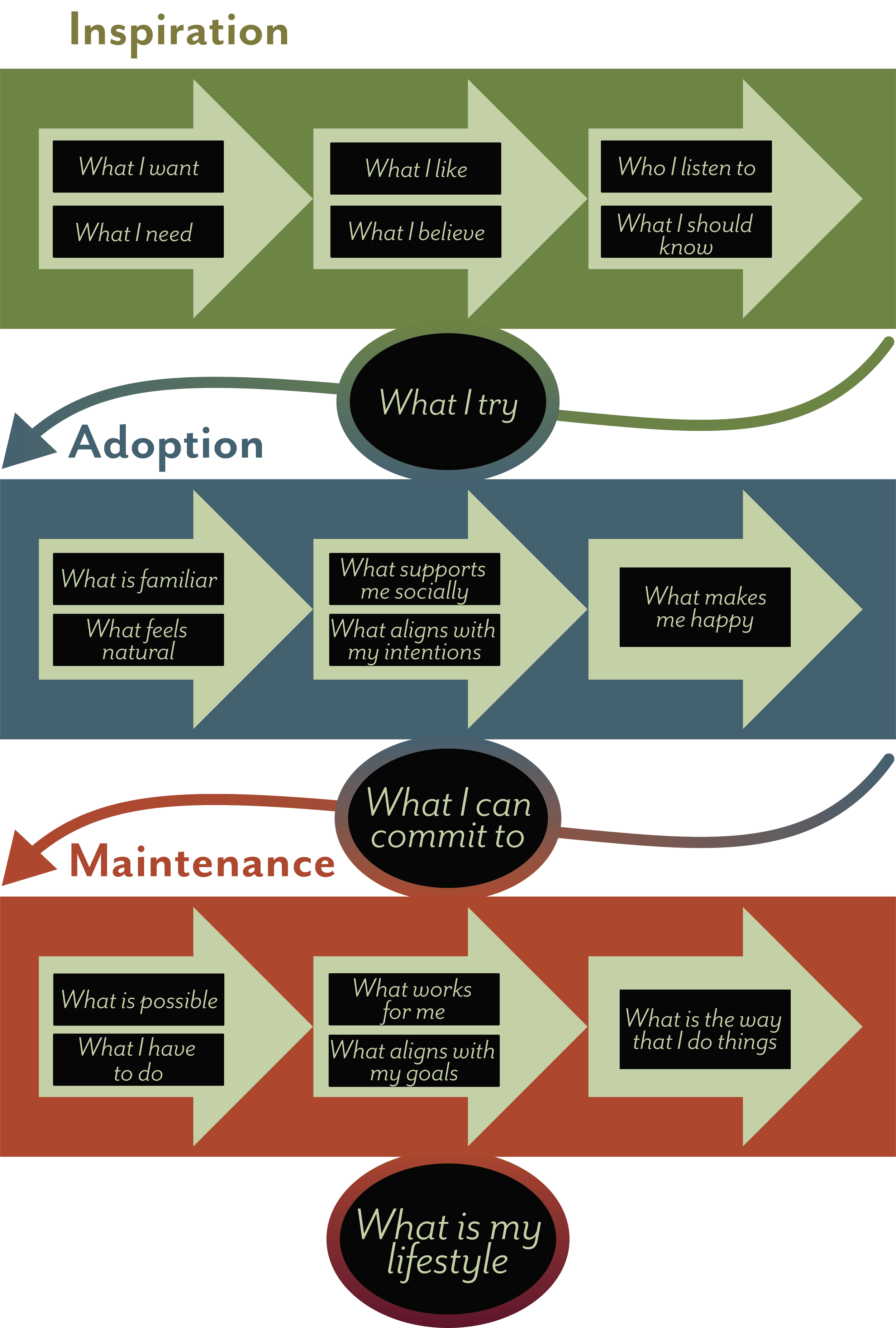

Participants were then asked to reflect on what initially drew them to these activities and how they maintain routines associated with them. Responses underwent an initial round of coding in Nvivo, informing the specifications of a user journey map organizing framework. Participants described their motivations for initiating lifestyle changes and integrating habits and practices into their day to day, the factors that supported the maintenance of these habits, and the needs and desires that prompted and sustained their engagement with wellness. The appearance of these themes in participant responses is organized at the left.

Figure 4. A framework for mapping the Wellness Journey. While sharing was included in initial versions of this journey map structure, participants did not discuss the sharing of wellness routines or practices in their responses to this question.

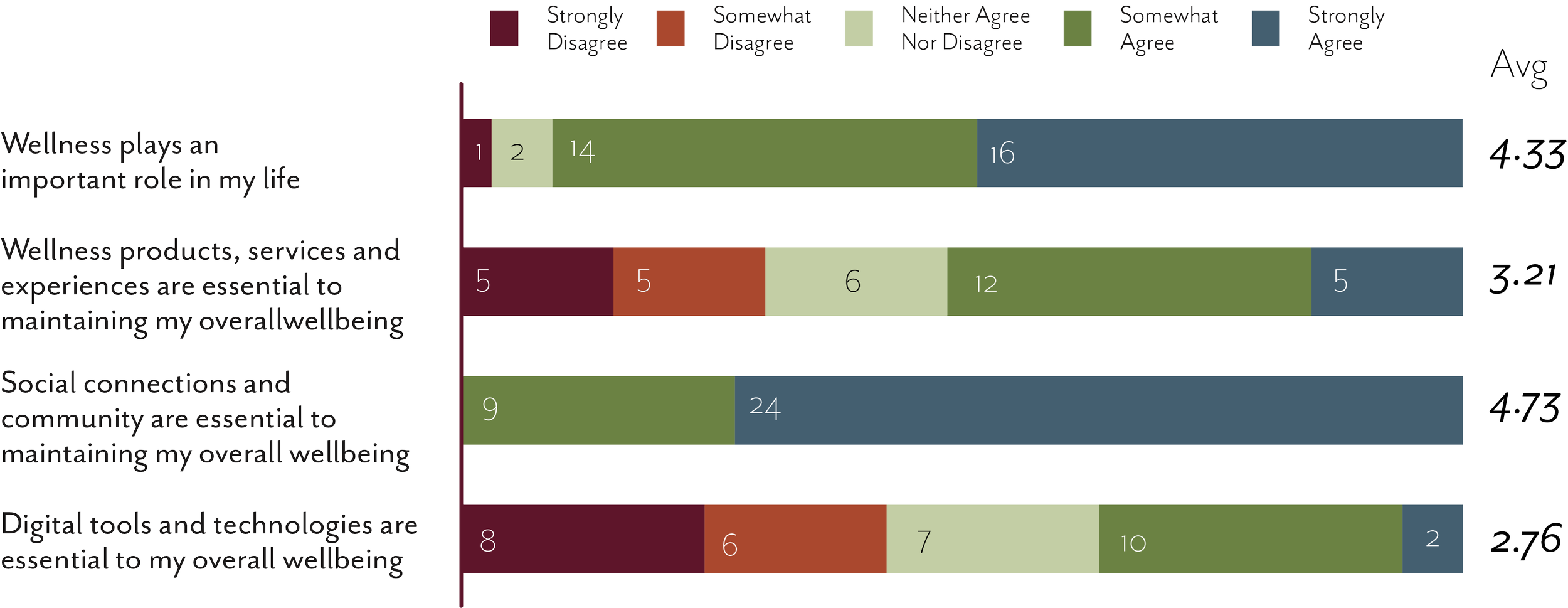

Figure 5. Participant responses to statements about the role of wellness in their lives.

To better understand the wellness goal setting mechanisms employed by young adults, participants were asked to describe their goals in their own words. Even for those who agree that wellness plays an important role in their lives, concrete goal setting is not a universal mechanism for maintaining wellness habits and states of wellbeing. Participants tended to describe their wellness goals in terms of habitual action, personal lifestyle philosophies and markers of health, which maps roughly onto the themes of wellness actions, wellness approaches, and wellness states of being that emerge across survey responses.

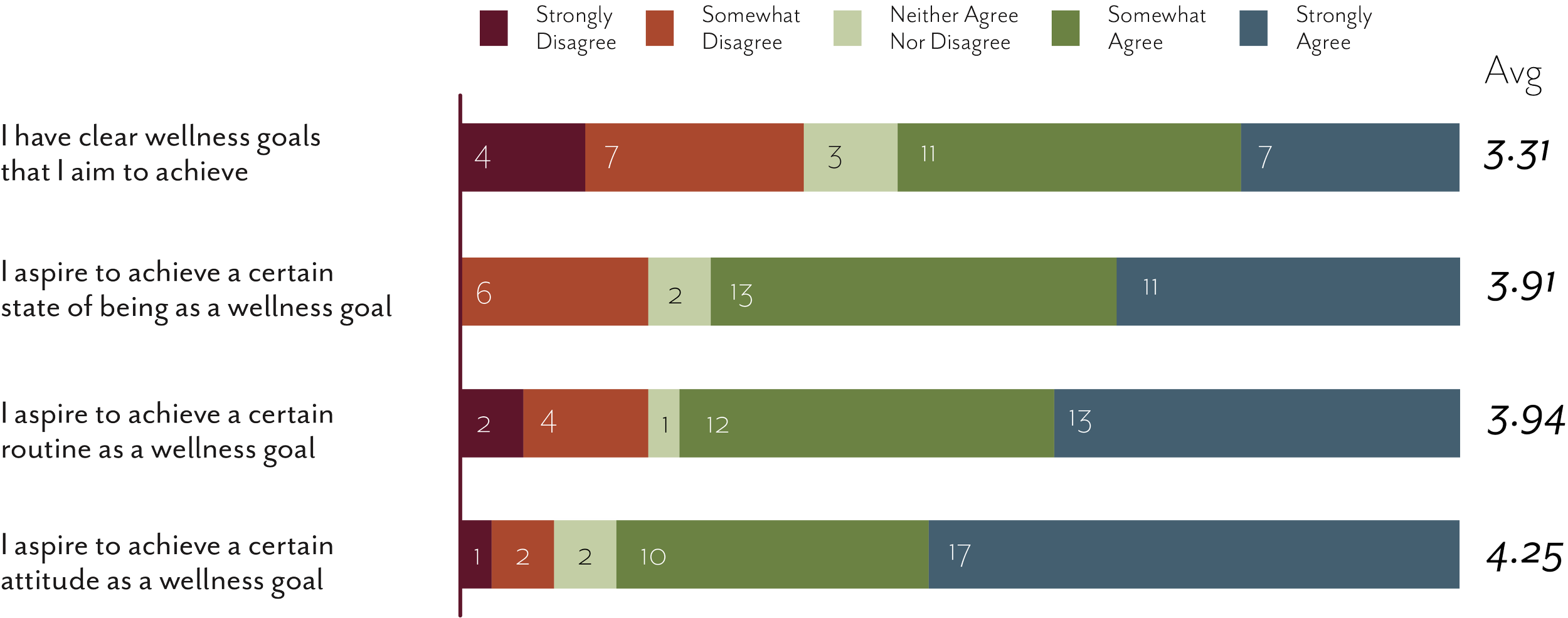

Figure 6. Participant responses to statements about their wellness goals.

Figure 7. Participant responses to statements about the barriers to their wellness.

Interviews

Figure 3. Popular wellness activities among survey respondents

-

Accomplishment 3

Relaxation 2

External Inspiration 2

Balance 1

Fulfillment 1

Intellectual Growth 1

-

Balance 11

Childhood Habits 6

Social Benefit 4

Boundaries and

Limitations 2

Paid Services 2

Scheduling 1

Small Wins 1

Spiritual Benefit 1

-

Self-improvement 7

Fun 4

Socializing 4

Optimization 2

Improved Wellbeing 2

In conjunction with insights from the pilot study, review of the literature, and an initial round of coding, the following journey map structure was identified and then used to explore the processes of integrating wellness routines, attitudes, and priorities into the lifestyle of young adults. The organization and thematization of these steps within the wellness journey can be viewed in detail in Appendix B.

Participants were asked to respond to a set of statements based on their experiences with wellness and healthy habit formation. All 33 participants responded to this set of statements, indicating whether they agreed or disagreed with each statement using a five-point scale, with 1 indicating they strongly disagree and 5 indicating that they strongly agree. Participant responses are summarized via the average response out of 5. The results of this section of the survey can be summarized at the right.

Survey respondents were in near universal agreement that wellness plays an important role in their lives. While social connections and community were broadly considered essential to respondents’ ability to maintain their wellbeing, wellness products, services and experiences (components of the wellness industry) were less central, with digital tools being the least important to respondent’s overall wellbeing. These results indicate that while maintaining wellbeing may be front of mind for many young adults, the degree to which participants engage with the wellness industry varies based on mechanisms they use to explore, adopt, and maintain new healthy habits.

Wellness Goal Setting

-

Accomplishment 3

Fitness 6

Diet 3

Sleep 3

Wellness Practices 3

Technology 2

-

Intuition 2

Balance 2

Reflection 2

Prioritization 1

-

Physical Performance 4

Mental Performance 3

Weight 2

Overall Function 2

Wellness goals were described in a very personalized manner, highlighting the importance of agreement between the lifestyle and circumstances of an individual and the goal-setting structure that works for them. As was indicated in the survey of respondents’ wellness activities, fitness is central to the actions that individuals consider central to their overall wellness. Participants highlight integrating some form of movement specifically, for instance, one respondent indicated the importance of “Making sure I move my body every day whether it’s a walk or a proper workout.” Wellness goals that fall into the Wellness Actions category tend to be simple, measurable, and focus on completing an activity goal. By contrast, goal setting that falls under the Wellness Approaches category are far more abstract in nature, highlighting a reflective approach to health and the development of a life philosophy of wellbeing. For instance, on participant notes, “I don’t currently set concrete goals, but I try to check in with my mental well-being daily & feel out what I might need in moments when I’m not feeling right.”

Wellness States of Being also have the potential to serve as measurable markers for wellness goal setting. Participants were primarily performance-oriented, especially when it came to athletic performance such as physical strength or speed. Others connected performance goals to other aspects of wellbeing, such as enjoyment or social wellbeing. One participant highlights this, stating that, “ I work to make sure I am in a good enough mental state to do things I like to do and be capable of helping people I care about.”

Following the open-ended portion of this section, participants were asked to respond to statements related to their wellness goals. 32 study participants (n=33; 97%) completed this section of the survey, indicating whether they agreed or disagreed with the statements presented on a five-point scale. The results of this section of the survey are summarized below.

Participant responses to the question of whether they set clear wellness goals were generally mixed. However, the framing of a wellness goal as the achievement of a certain attitude was met with highly positive responses from participants, with 27 respondents (84%) saying they somewhat or strongly agree with the statement. The framing of wellness goals as achievement of a certain state of being or routine were also generally positive. While a healthy state of being or maintenance of a routine can be translated into measurable goals, the development of a healthy attitude is markedly less quantitative. As a result, this may pose a challenge for those hoping to achieve improvements in their overall attitude and mindset to set clear goals for themselves. This may point to the use of routine-based goal setting as a mechanism for re-enforcing positive attitudes indirectly.

Barriers to Achieving Wellness Goals

Participants were asked to respond to statements about barriers to achieving their wellness goals. 32 study participants (n=33; 97%) completed this section of the survey, indicating whether they agreed or disagreed with the statements presented on a five-point scale. The results of this section of the survey are summarized at the left.

Overall, participants had weaker agreement with this set of questions. Affordability, though still important to some, was not communicated as a universal barrier to achieving wellness goals. Participants demonstrated slightly more concern for the role of a busy schedule and internet/cellphone usage in creating barriers to wellbeing.

A total of six (n=6) interviews were conducted. Responses were organized in a journey map (Appendix C) based on the one in Figure 4. For ease of understanding and preservation of anonymity, participants are assigned labels A – F.

When asked what initially drew them to their wellness habits, participants described the way that interactions between the external environment and their internal needs and desires shaped their exploration of new routines, practices and even attitudes around their health. Inspiration that arose from interacting with others often involved a trusted network, such as family or community. Participant B highlights this, describing their experience as follows:

…Freshman year, I was actually in the engineering learning community, so I was surrounded by a bunch of guys, and half of those guys were gym bros, and they’re like, oh my god, everyone should be going to the gym, everyone go now! So I was influenced that way, because I was like, why not? All these people are going, I could also go too, regardless. I guess it was nice that I had people that were nice enough to show me what to do at the gym, and we’re nice enough to tell me if what I was doing is wrong. (Participant B)

Trust is an important part of the initial stage of adopting a new wellness routine, with participants highlighting the value of past success and the wisdom and experiences of those that are close to them.

In addition to the knowledge gathering and influence that supports the initiation of healthy habits, many of the interviewees noted the importance of addressing personal needs – particularly those that support broader life goals and success in the areas that matter to them. Participant E articulates this idea as follows:

…when I got into college, I realized how much physical activity actually helps my brain work better, so if I do care about, I don’t know really being present and able to think, then I need to… also be strong in my body. (Participant E)

This sentiment is echoed by Participant C, who expresses the alignment of their hobbies with their overall wellness:

I think it’s mostly personal, I do ski in the winter and dry land training would be great just to be able to last longer on the slopes, I think that’s honestly a big motivator of it that I’ve started working out at home. (Participant C)

As opposed to a process of concrete goal setting, participants respond to a combination of internal and external factors, seeking alignment between their ideal lifestyle, focusing on both their responsibilities and their hobbies, and their day-to-day wellness choices. Self-knowledge and trusted social networks are also significant in shaping the initial stages of incorporating healthy routines into one’s life.

After exploring their initial motivators for testing possible tools to improve wellbeing, participants discussed their experiences with adopting new routines into their lifestyle. Some participants stressed the value of social accountability, for instance, Participant E noted that,

Social accountability helps strengthen what you might already feel discipline-wise…I know that I want to feel stronger, and that’s the work that I have to do to feel that way. But actually doing the work is a lot easier when there’s other people right there with you doing the same thing.

This sentiment is echoed in other circumstances, such as commitment to academic goals and work-life balance, as described by Participant F:

It seems like as time went on in school, I found my friends that I would study with, and do homework with, and all this stuff and that makes work a lot more palatable. And with school not being this crazy, stressful thing anymore, I feel like I could spend more time doing a lot of other things, and I’m just generally happier because of it. (Participant F)

Social networks play an enormous role in the practicality of lifestyle change. Participants also noted the role of journaling and check-ins as an alternative or compliment to this process. The medium of writing serves a similar function in holding one accountable for their actions.

When it comes to the adoption of new routines, participants remarked a lot on the effectiveness of goal setting strategies. Not unlike the results from the survey, participant goals are largely routine based rather than built around physical markers of health. Furthermore, participants were also thoughtful about how mood impacts their ability to commit to their routines and noted that some goal setting strategies do not account for this. Participant D highlights the way external factors influence how they engage with their healthy habits:

I would love to have a plan or routine, but again, I’m so bad with it… the only way I can really keep a plan or routine is if there’s another person. Like, sometimes now I’ll climb with someone, and that’s like, okay, we’re doing this on this day. Sometimes I have that regularly, like we go on Mondays, but If it’s just me, I can’t really make myself do anything that I don’t want to do. It kind of has to be intuitive, like if I really feel the need to do this today or I have this chunk of time, and that would feel good. (Participant D)

Participant D articulates an intuitive approach to wellness that connects with their social needs and the goal of feeling good while engaging in the healthy behavior rather than as a reward for it. This is further discussed by Participant E:

I think the biggest thing that helped was when I reframed how I think of goals, and how I think of what I want for myself… I feel like that change is what took me from what can I buy to lose weight, or, like, what can I do to make my skin clearer – It’s more like… what are the behaviors that go along with those things? And if those things make you feel better, or get you in a healthier place, do those things consistently because of how they feel – the process of doing it, rather than being so driven on achieving. I feel like that really helps. (Participant E)

One key insight here is that instead of routines being highly regimented, participants largely sought out what could be integrated into their lifestyle seamlessly, while still keeping in mind the potential for longer term results.

The long-term maintenance of a wellness routine or healthy habit is essential for a sustained positive impact of overall wellbeing. Participants noted a variety of key mechanisms that allow for this sustained impact to take shape. Participant A used the term “automate” to describe the complete integration of a habit into one’s lifestyle. This process of automation takes the mental effort out of maintaining one’s healthy habits which can open up opportunities for other practices towards self-improvement. Record keeping habits such as journaling can also have a positive impact on the process of maintaining healthy habits. For instance, Participant B noted their use of Excel to record workout splits. The record-keeping styles described by participants tended to align with whether they took an intuitive, intentional, or mixed approach to the maintenance of their habits. The recognition of one’s particular wellness style may inform what steps are most effective for integrating more impactful healthy habits into one’s lifestyle.

Participants also discussed roadblocks that inevitably arise that disrupt their positive routines. Participant E highlighted the reality of mental health struggles and the way they impact self-discipline. Participant F expressed similar feelings, stating that:

Whenever I am going through a really tough time, like a tough semester, or finals week, I long to be consistent again, and unfortunately, when times get tough, I kind of veer off the path of self-help and just kind of focus more on school and stuff, which isn’t good. Right now, I’m at a point where, if I do that, I still do pretty well in school. (Participant F)

Participant F’s experience highlights both the inevitability of variation in one’s commitment to routine as well as the long-term benefit of maintaining healthy habits when it is easier to carry one through more challenging times. The importance of balance was a common theme across the survey and is crucial for the prevention of burnout.

Given the role of community and social accountability in the initiation, adoption, and maintenance of wellness routines, sharing is evidently a crucial part of the wellness journey. That being said, participants were not asked explicitly about the process of sharing their wellness experiences as both the survey and interview protocols were designed to be succinct and focus on the more personal dimension of the journey towards improved wellbeing. Ultimately, sharing knowledge and experiences, whether interpersonally or in a public forum, is an important part of generating interest and seeding inspiration in those looking to enhance their overall holistic health.

Inspiration

Adoption

Maintenance

Sharing

Discussion

The purpose of this survey and interview-based study was to identify the most effective mechanisms for incorporating sustainable wellness habits into the lifestyles of young adults. Participants in both phases of the study were invited to share and discuss their thoughts on the nature of wellness and its role in their lives. This inquiry offered an abundance of unique perspectives revealing how young adults establish individualized philosophies of wellbeing that engage with and extend beyond the offerings of the consumer market. Using design research strategies, we can explore how their lived experience might inform a design framework for meaningful personal transformation rather than unwieldy consumption behavior.

The central hypothesis stated in the introduction of this paper was that solutions that transform and personalize wellness products and services through creative practices and social engagement offer more effective and sustained healthy habits. While the social dimension of wellness cannot be overstated, the impact of its creative aspect is more subtle. Creative practices are useful for some, but it is self-exploration more broadly that supports the successful integration of wellness routines into the day-to-day life of young adults. That self-exploration might be enhanced through responsible engagement with media, but the use of social media and absorption of digital content can also create roadblocks in the navigation of opportunities for person transformation.

Processes of Inspiration and Initiation

For a significant number of participants in this study, the seeds of routine and habit formation were sown in childhood, making sustaining those healthy habits a largely intuitive and automatic process. Generating a lifestyle based on long-maintained practices solidifies their enduring presence and positive impact on overall wellbeing. Within the age range of this study, 18 to 34, participants may be in the early stages of distinguishing themselves from the family or well into establishing their own. In either case, study participants were no stranger to change in life circumstances; even as they draw from their experiences in childhood, they tend to seek continuous improvement to their wellbeing and respond to changes to their physical, mental, emotional and spiritual needs as they arise.

A significant part of this process is the consideration of one’s beliefs and preferences when information seeking to better meet one’s fundamental needs. In a media-saturated world, exposure to wellness information is an inevitability for many, propped up by the widespread popularity of fitness and nutrition content and the influence of the enormous industry that this content operates in service of (Cavusoglu & Demirbag-Kaplan, 2017). Young adults might combat passive absorption of that information by engaging more critically with their environment, where interactions with other people, cultures, and ideas can inform individualized perspectives on personal transformation.

The initiation and inspiration phase of the wellness journey is also characterized by the engagement with a continuum of needs and desires. This recalls the opposing logics of wellness explored by Colleen Derkatch, with participants angling to use wellness routines to address their needs through a process of restoration as well as realize their desires through physical, mental and spiritual enhancement (2018). While these processes seem to serve as a backdrop for participant engagement with new routines, hobbies, or practices, it is also worth noting that individuals may be drawn to activities simply because they are enjoyable in the moment. The prospect of fun and development of personal preference are also important loci of movement of the lifecycle of healthy lifestyle development.

Processes of Adoption

Participants in this study noted how they gravitated towards that which is familiar or natural to them. As discussed previously, familiarity reduces the barrier to entry for the adoption of routines and practices. The degree to which these routines and practices feel “natural” is also significant and allows individuals to build habits through the necessary patterns of everyday life. Journaling practices were often cited as a multi-functional method for organizing and reflecting on those patterns, a means of both recording one’s patterns and behaviors, as well as a wellness tool in and of itself, for the management of racing thoughts or as a creative outlet. The most successful integration of healthy practices into the lives of young adults appears to emerge when those practices are not simply a means to an end but support an individual’s holistic wellbeing through action and process.

For example, participants indicated that they strongly considered wellness options that fulfilled certain social needs or aligned deeply with their sense of self and internal system of values. Particularly in the realm of fitness and exercise, the overlap of physical and social needs makes making time for healthy habits easier. Developing a strong understanding of oneself and what makes for a practical and balanced lifestyle was also expressed as an important mechanism in the successful adoption of new wellness routines. For instance, several participants noted changes they sensed when neglecting certain dimensions of their life and how this perception motivated them to return to a baseline that aligns with their needs. While not discussed explicitly in participant surveys, the conversations that arose in interviews highlighted the way in which overuse of technological and media distractions can disrupt the awareness of the needs and desires that motivate positive change.

Processes of Maintenance

Long-term maintenance of wellness routines is anchored by necessity; however, participants also communicated the importance of balance in sustaining a healthy lifestyle. Creating the conditions for more seamless integration of wellness practices into one’s day-to-day life is a common method used to necessitate participation in healthy habits. For instance, an up-front membership cost or social accountability were cited as factors that necessitate the maintenance of routines. This “investment” in one’s overall wellbeing may not provide immediate returns in the form of performance improvement or pleasurable experience, however, an understanding that healthy habits are an investment in one’s self creates the foundation for sustained lifestyle change.

The value of goal setting is present across the phases of the wellness routine integration process and can be particularly instrumental in supporting the maintenance of healthy habits. Though participants had varied goal setting strategies, many cited the value of routine-based, achievable goal-setting strategies that could be maintained long-term. Flexibility was also favored by many participants, with the freedom of choice accommodating shifting moods and energy levels. Certain aspects of one’s lifestyle are more fixed than others, with work and school often described as persistent responsibilities that form the contours of one’s schedule. As a result, wellness might be a priority that fills the gaps in daily responsibilities while simultaneously supporting the capacity to seek alignment between actions and intentions in other aspects of life, including academic achievements, career advancement, financial stability, relationship health, spiritual practice and any number of other forms of personal fulfillment.

The more alignment an action or process has with a person’s goals, the more likely they are to integrate it wholly into their lifestyle. Ultimately, when wellness habits or routines become the way that someone does things, the easier it is for those practices to become a sustained part of who they are. The most effective tools and methods for sustained personal transformation might find a way to embrace this, possibly with the help of digital technology. However, in a world where there is an app for everything, how might we design for transformation in a way that resists the commodification of wellness and supports the social and creative development of individuals?

Notes on Sharing

Initially, sharing was included as a key step in the lifecycle of wellness routines. However, its role wasn’t explicitly explored in either the survey or interviews and was thus often left out of much of the data. The way individuals share their experiences with wellness, either in-person or online may warrant additional exploration. The idea of “sharing” in contemporary wellness cultures is increasingly relevant as users adopt strategies to resist influence and combat misinformation.

The Wellness Journey

Insights from each phase of the wellness journey can be organized as part of a process of self-discovery – where individuals build out a sustainable healthy lifestyle through deeper self-understanding.

These phases in the wellness journey map roughly onto the three themes that shape the definitions of wellness and the goal setting strategies that support them, namely wellness states of being, wellness actions and wellness approaches. We might then consider how the process of integrating and sustaining healthy habits into our lives begins with an idea of what it means to be well, where we imagine an idealized state of wellbeing based on our unique needs, desires, beliefs and circumstances. This is realized through actionable lifestyle changes that are supportive rather than disruptive. Finally, as those individual actions become a long-term commitment, we can establish a meaningful approach to, or personal philosophy of, living well, which becomes a part of our lifestyle long term and even something that can be shared with others.

Figure 8. The Wellness Journey Framework

Figure 9. Combining definitions of wellness with the Wellness Journey Framework

Intuitive Versus Intentional Approaches

Working through these processes in conversation with interview participants further revealed the varied mindsets and mechanisms that support the development of sustainable wellness routines. In addition to upholding the findings from the survey regarding the value of self-discovery and self-knowledge, interviewees expressed a range of approaches from highly intuitive responses to physical and emotional needs to more regimented, scheduled daily routines. Both wellness styles benefit from previously discussed factors such as social accountability, balance, and alignment between actions and goals. Where they diverge is in the expression of routine in an individual’s day-to-day life. While those with an intuitive approach thrive when provided options, the intention-oriented schedulers prefer the simplicity of a daily routine. As discussed by several participants, this orientation is not fixed, and one’s overall wellbeing and state of mind can disrupt habits and patterns for better or worse. As a result, wellness tools, such as journals and trackers, should accommodate this range of wellness styles, as well as provide space for the self-reflection required to identify which approach best accommodates an individual’s needs, natural tendencies, and external circumstances.

Prototyping

The Wellness Journey Framework provides summary of the processes of self-inquiry which generate effective and individualized approaches to wellness in individuals seeking lifestyle changes. As explored in Thompson & Troester (2002), contemporary wellness practices are highly fragmented, reflecting the patchwork of information, values, and media consumers are exposed to. The process articulated in the Wellness Journey Framework highlights the individualized and fragmented nature of wellness in the lives of young adults, where the emphasis does not lie primarily on principles of a common culture shared among a community but on the unique needs of individuals and the processes by which they come to understand them. Drawing from this discussion, I propose the following framework for an analog journaling protocol that supports user self-discovery and the implementation of effective and sustainable healthy habits that do not necessitate overconsumption or the use of digital technology. However, the prompt-based structure could lend to the development of a digital application with even broader functionality if desired.

The steps identified below are based on qualitative data from both the survey and interview phases of this study. Further research and evaluation of this framework would be required to assess the timeline and effectiveness of the methodology.

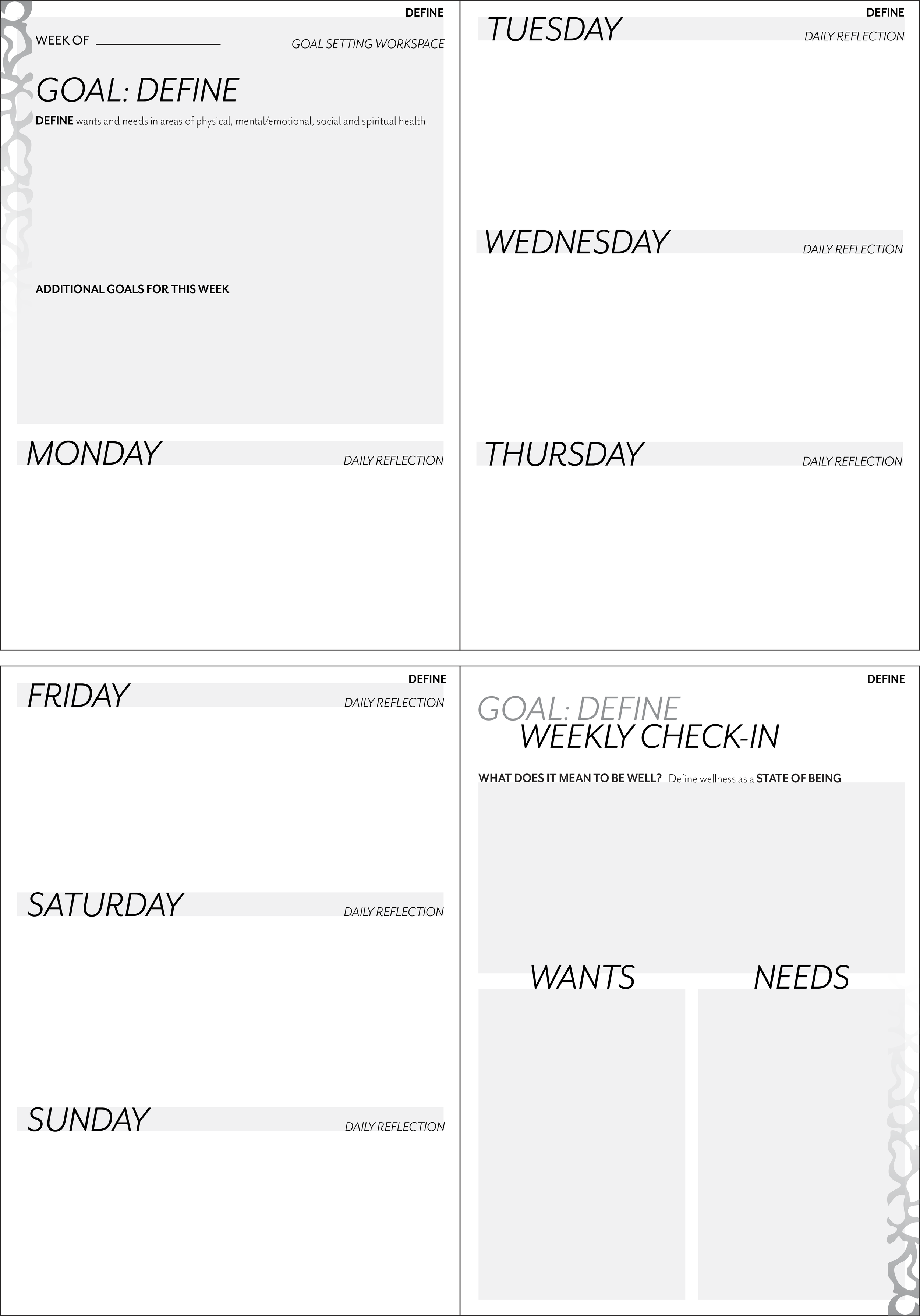

Phase 1: Inspiration & Initiation

A. DEFINE wants and needs in areas of physical, mental/emotional, social and spiritual health. Use these to build an understanding of wellness as a state of being.

B. CATALOG beliefs and preferences to better understand possible avenues towards achieving a state of wellbeing, as understood in the DEFINE stage.

C. RECORD potential advice and health information that is intriguing or aligns with your interests and intentions.

Phase 2: Adoption

A. CONSIDER what fits naturally into existing lifestyle patterns and that which is familiar. These considerations may reveal avenues towards improved wellness that present the least friction.

B. EVALUATE newly implemented wellness actions based on goals identified in the DEFINE stage as well as the impact of these actions on your social and emotional wellbeing.

C. REFLECT on how new routines and practices have impacted your overall happiness.

Phase 3: Maintenance

A. REASON about how realistic it is to maintain routines long term. Is your approach sustainable?

B. ESTABLISH the presence of practices that work for you in your day-to-day life. Understand and reflect on the values that you explored in the EVALUATE and REFLECT phase.

C. REALIZE a new approach to wellness that fits seamlessly into your lifestyle and supports the wants and needs you outlined in the DEFINE phase.

These three phases, arrived at through the primary research, would serve as the anchor for a more traditional dual-purpose daily planner and journaling process, during which the user would determine if they tended towards a more intuitive or intentional approach to their daily and weekly schedule. Variations in the approach can be summarized as follows:

Phase 1: Inspiration & Initiation

Determine intuitive or intentional approach through consideration of existing habits and routines. Record weekly activities to understand cadence of participation in routines. Attempt scheduling a week in advance as well as a more flexible approach. Record changes to responsibilities. Are these predictable?

Phase 2: Adoption

Based on intuitive or intentional approach either prioritize recording your daily habits and creating an action-based weekly goal-setting strategy (intuitive) or planning out your week based on your goals and check off your habits as you execute them.

Phase 3: Maintenance

In both approaches, pair or replace action-based goals and records with reflective writing as habits become an automatic part of day-to-day life.

Limitations & Future Directions

Figure 10. A sample two-page spread reflecting prompts from Phase 1 - Step A: Define

Qualitative research conducted as part of this master’s thesis was done in service to the development of a design framework that specifically centers the support of individual journeys towards improved holistic health and wellbeing. As a result, certain research questions, particularly those surrounding the role of digital media in the wellness experiences of young adults and the impact of the commodification of wellness on the perception and implementation of healthy lifestyles remain only partially answered. For instance, this work does not comprehensively identify the prevalence and scope of the impact of digital technology on the wellbeing of young adults. Similarly, in-depth analysis of participant experiences with the commodification of wellness in our consumption-based culture and society is relatively confined to secondary review of the literature. With a larger sample size, and thus a more abundant and diverse range of perspectives, participants’ experiences with digital technology and commodification could reveal themselves. Alternatively, complementary qualitative research could be conducted as a foundation for service and product design, creating a baseline for identifying more specific design problems and even evaluating products and services already on the market.

The boundaries of the “young adult” demographic are admittedly somewhat arbitrary. We culturally understand young adults to be those in their late teens and twenties, and occasionally even those in their early thirties and beyond. However, college students, young professionals, and parents of young children tend to fall within this age range, with incredibly varied life experiences and circumstances that affect their wellbeing. Further research may be served by refining the target demographic further, understanding with more precision how individuals find ways of making time for wellness practices in their lives despite the distinctive limitations they face. Furthermore, the sampling methodology employed in this study most likely skewed towards a professional, college-educated population which further privileges wellness as a concern mainly of the middle and upper classes. The collection of demographic information such as income, education, gender, and race might help to identify weaknesses in sampling.

Longitudinal research on the transformation of wellness perspectives and the effectiveness of existing or novel wellness interventions should be conducted. Such longitudinal work could also serve to enrich this body of work and support design problem solving. Self-reported participant experiences of the effectiveness of their habits and routines is valuable, but finding meaningful ways of measuring change would be the logical next step in bolstering the theories put forth in this work, particularly around the role of social engagement and creative practice in supporting “decommoditized” wellness. Ultimately, this master’s thesis provides a starting point for identifying the problem of a dizzying and fragmented wellness industry and suggesting strategies for personal transformation.

Works Cited

Badr, S. (2022). Re-Imagining Wellness in the Age of Neoliberalism. New Sociology: Journal of Critical Praxis, 3. https://doi.org/10.25071/2563-3694.66

Baker, S. A. (2022a). Alt. Health Influencers: How wellness culture and web culture have been weaponised to promote conspiracy theories and far-right extremism during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 25(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/13675494211062623

Baker, S. A. (2022b). Wellness culture: How the wellness movement has been used to empower, profit and misinform. Emerald Publishing.

Cavusoglu, L., & Demirbag-Kaplan, M. (2017). Health commodified, health communified: Navigating digital consumptionscapes of well-being. European Journal of Marketing, 51(11/12), 2054–2079. https://doi.org/10.1108/ejm-01-2017-0015

Coffey, J. (2024). ‘Having it All’: Wellness Culture, Instagram Bodies and ‘Perfect Lives’ in a Time of Global Ecological Crisis. In N. Smith, C. Southerton, & M. Clark (Eds.), Researching Contemporary Wellness Cultures (pp. 153–165). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-80455-584-220241011

Creswell, J. (2008). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (3rd edition). SAGE Publications, Inc.

Derkatch, C. (2018). The Self-Generating Language of Wellness and Natural Health. Rhetoric of Health & Medicine, 1(1–2), 132–160. https://doi.org/10.5744/rhm.2018.1009

Dunn, H. (1959). What High-Level Wellness Means. Journal of Public Health / Revue Canadienne de Sante’e Publique, 50(11), 447–457.

Featherstone, M. (1982). The Body in Consumer Culture. Theory, Culture & Society, 1(2), 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/026327648200100203

Grénman, M., Hakala, U., & Mueller, B. (2019). Wellness branding: Insights into how American and Finnish consumers use wellness as a means of self-branding. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 28(4), 462–474. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-04-2018-1860

Grénman, M., Hakala, U., Mueller, B., & Uusitalo, O. (2024). Generation Z’s perceptions of a good life beyond consumerism: Insights from the United States and Finland. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 48(1), e12994. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12994

Global Wellness Institute. (2024). United States Wellness Economy Now Valued at $1.8 Trillion – The Largest Wellness Market in the World [Press Release].

Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687